For years, EU has stressed upon its open trade rules and regulations, positioning itself as a good region to do business with. Now, however, this claim is a matter of contention. EU’s soon-to-be-implemented Carbon Border Tax stands in the face of disagreement from several nations, and reasons are many. In practice, the CBAM is a fee charged for emissions embedded in products imported to the EU.

Why is CBAM facing backlash?

The EU is a key export market for emerging economies, where production tends to be more emission-intense due to widespread use of emission heavy production processes. As the bloc solidifies its plan to implement a carbon border tax in the form of CBAM, several developing as well as developed nations have voiced concerns about CBAM and its discriminatory nature. The BASIC group of nations (Brazil, South Africa, India, and China) said in a statement, “unilateral measures and discriminatory practices, such as carbon border taxes, that could result in market distortion and aggravate the trust deficit amongst Parties, must be avoided.” But what exactly is it about CBAM that is discriminatory? The answer lies in the Article 4(3) of the Paris Agreement, to which EU nations are signatories. The article roots itself in the principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibility (CBDR) which states that while all nations are responsible for addressing the climate crisis, they are not equally responsible. Responsibility must be assigned with the countries’ levels of economic development in view. CBAM not only goes against this principle, but also puts less developed nations at a greater disadvantage by levying a carbon tax proportionate to the intensity of emissions embedded in the production process.

How will CBAM affect India and its businesses?

In 2020-21, 17% of all Indian exports totalling up to $35 billion were to the EU, making it India’s second-largest export destination. $2B of these exports from India come from Iron, Steel and Aluminium and fall squarely under the ambit of CBAM levies. Most of these exports consist of iron and steel in their primary forms (and other processed products such as tubes and fittings, structures, and railway materials) and unwrought aluminium, aluminium powder. All of these are strategically important for India. Under the current scope of CBAM, the impact to Indian industry may be limited to the exports of iron and steel and aluminium, as India does not export cement, fertilisers chemicals, or hydrogen to the bloc.

More carbon intensive production equals higher carbon adjustment

To understand why the steel and iron industry is exposed to risk under the new regime, it is important to take note of CBAM’s treatment of relative carbon intensity. Countries with cleaner production processes stand to gain competitive advantage. Under EU’s Emissions Trading System, companies are offered free allowances to emit carbon and this limit is reduced every year. CBAM requires the importer of goods to purchase certificates to cover the emissions embodied in the imported goods. The producer’s actual emissions determine the amount of certificates required.

This is a critical issue for the Indian steel industry because of its high emission manufacturing processes. While globally 1.39 tonne of carbon is emitted for the production of 1 tonne crude steel (denoted as T/tcs) , the Indian average is almost double that, at 2.67 T/tcs. This leaves Indian steel at a disadvantage since major global exporters such as Russia, South Korea, and USA, manufacture steel using low-carbon processes, making the product cheaper for businesses to import into the bloc.

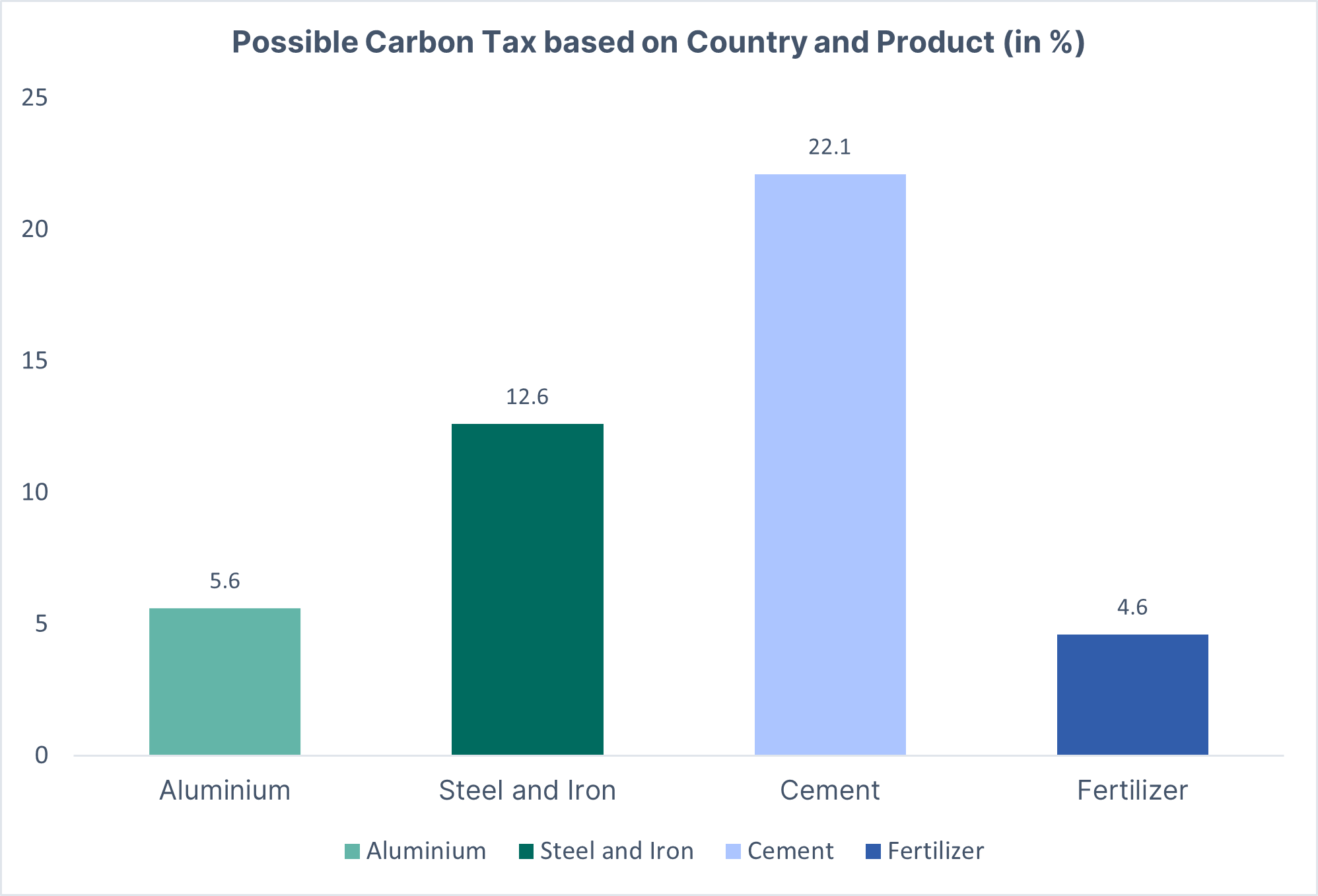

The emission heavy steel production makes this a very hard-to-abate sector, alongside other emissions intensive production sectors – cement, aluminium, and fertilisers. Assuming that the price of one carbon certificate is $44, the table below reflects possible carbon adjustments based on countries and products. The numbers in the table can be read as possible additional tariffs for companies if they choose to import the products from India, proportionate to the emissions embedded into these products.

The imposition of CBAM will result in increased financial and administrative burden on Indian goods. Thus, a sizeable portion of India’s exports to the EU will run the risk. In fact, according to the UNCTAD, India risks losing $1-1.7 billion in exports of goods like steel and aluminium due to their energy and emission intensive manufacturing processes. For reference, India’s exports of steel and iron to EU were valued at approximately $5 billion in 2021. This is consistent with general predictions that a USD 30 tax per metric tonne of CO2 emissions may cut overseas producers’ earnings by around 20%. Given that EU steel producers will also face the phaseout of free carbon permits just as the new regime is implemented, the sector’s domestic carbon costs will start rising sharply in 2026.

CBAM seeks to utilise market-based measures to drive innovation and even force companies to abate the climate emergency. In 2026, CBAM will expand its scope to all products, giving industries and countries time to work on internal net zero policies, such that universal implementation does not send shockwaves through economies. If implemented equitably, the mechanism may serve as a nudge for countries and businesses to disrupt business as usual. While the principle of CBDR must apply to any ramifications with impact that echoes globally, it is critical to highlight that India positions itself as a political and economic power, with ambitious net zero goals, and businesses and governments must contribute to those goals.

The next step for businesses would be to assess the impact of CBAM on their products and make amendments to production processes and supply chains, in order to minimise risk. Once the transitional period is over in 2026, more industries will be brought under the scope of the regime. Industries may treat this period as an opportunity to reduce the carbon emissions and stay competitive in the international arena. It’s not all doom and gloom for Indian exporters though – at least not if invest in R&D to decarbonize production processes. Keep following us for the next article on what Indian businesses need to do to minimize the impact of CBAM – as the EU gradually increasing scope of industry coverage.

References:

The-EU-Carbon-Border-Adjustment-Mechanism-Implications-for-India.pdf (euindiachambers.com)

pbrief_cbam_sl_21.4.21.pdf (cer.eu)