Moving towards the ‘point of no return’

Climate change is a critical barrier to the overall growth and development of a nation. The rising temperature and unpredictable weather patterns not only impact ecosystems and societies but also influence how businesses are operated. For instance, India incurred a 5.4% loss in its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 2021, particularly in certain sectors including manufacturing, services, construction, and agriculture due to severe heatwaves. Such changes in weather patterns expose businesses to physical and transition risks, reduce profit margins, and limit their potential to become climate resilient. At the same time, businesses are major contributors to domestic GHG emissions. For instance, Indian industries consume over half of the total electricity produced in India, which further contributes to 40% of the overall domestic GHG emissions.

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) suggests that by reducing 60% of emissions by 2030, industries can slow down the climate crisis. Indian businesses are uniquely positioned to become key drivers in abetting climate change by transitioning to climate friendly technologies and practices. While some Indian companies are adopting low-carbon pathways, many others are yet to take voluntary action to increase their sustainability quotient. This push to reduce emissions places a special impetus on decarbonisation – the fundamental process of reducing or removing emissions from the atmosphere.

India has made commitments to reduce its emissions on various international platforms, including voluntarily pledging its Nationally Determined Contribution to reflect a reduction in carbon emission intensity of its GDP by 45% and generate 50% electric power from renewable energy sources by 2030. This force of national and international commitments, along with climate-conscious investors and consumers pushes the Indian industry to adopt decarbonisation approaches. Lowering emission will help companies in achieving net-zero targets.

Why should industries care: climate-linked corporate risks

While the overall economy of a nation is impacted by increasing GHG emissions, energy companies, banking, and insurance companies, as well as interdependent supply chains are particularly vulnerable to direct and indirect risks due to climate change. These sectors are susceptible to financial and non-financial losses making it critical for them to identify ways to strategically decarbonise their operations.

The climate-related risks can be broadly classified into physical risks and transitional risks.

1. Physical risks arise from changing weather patterns and temperatures that impact businesses. The frequency and severity of physical risks such as heatwaves, cyclones, droughts, and floods are becoming increasingly difficult to predict. For instance, wildfires have led to companies incurring losses due to obstructions and forced closures of raw materials sourcing sites; which in turn has caused quantifiable disruption in their manufacturing processes, supply chains, and employee health.

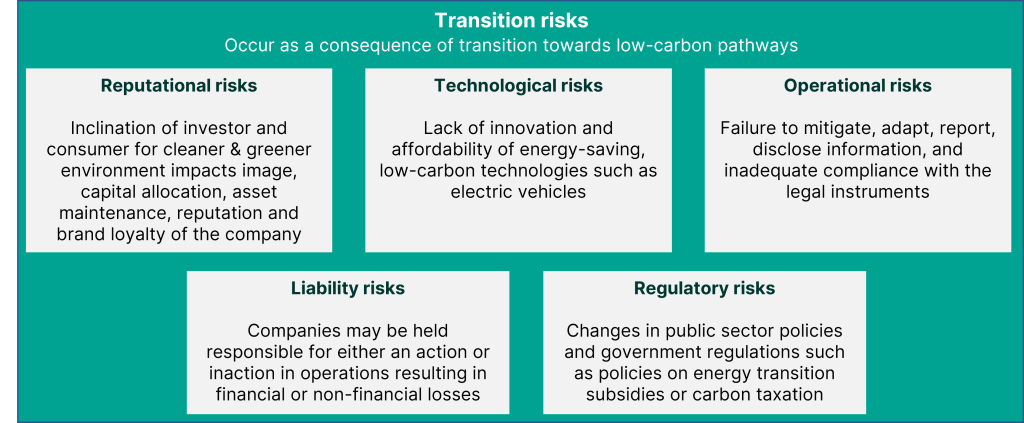

2. Transition risks are a consequence of not shifting to a low-carbon economy, with various determinants playing a role in the severity of risk experienced by companies. Banks and insurance companies are particularly exposed to transition risks. They tend to closely monitor, anticipate and incorporate changes in their business models corresponding to potentially emerging risks. However, the scale and nature of climate-related physical and transition risks still affect them adversely and this uncertainty further exacerbated by geographical diversities.

Greater access to clean industrial transformation can lead to increased environmental and social sustainability. By ensuring robust monitoring and reporting of their decarbonisation journeys, companies can establish their credibility in the eyes of government, consumers and investors.

Companies must adopt decarbonisation pathways

While India is taking positive affirmative actions to mitigate emissions, certain energy-intensive sectors like steel and petrochemicals hold ethical responsibility of committing to decarbonisation goals.

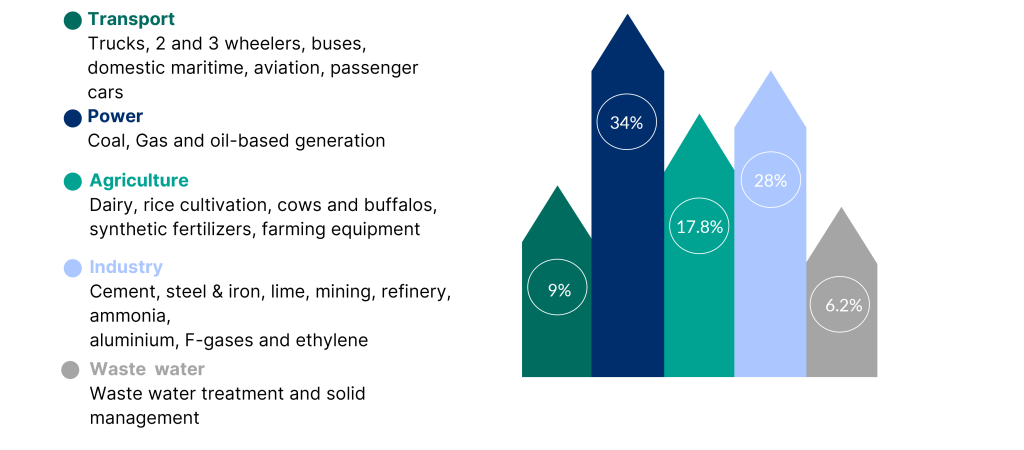

India is the third-largest carbon emitter globally as it releases 2.9 gigatons of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e) every year as of 2019. About 70% of these emissions are driven by these major sectors: power, industry, agriculture, automotive, water and waste management, and building construction.

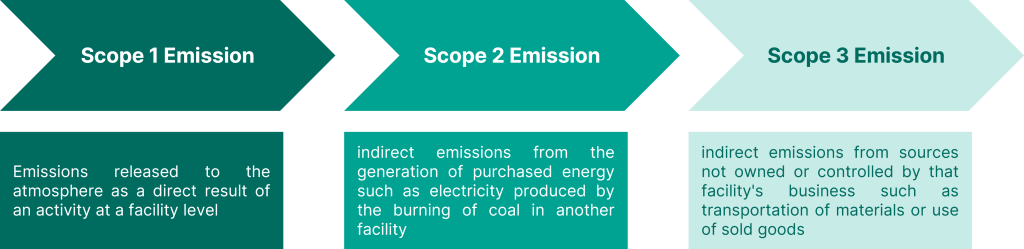

Based on a company’s operation, the level and nature of carbon emissions in its value chain varies. These can be categorised as scope 1, scope 2 and scope 3 emissions.

As it is becoming increasingly important for businesses to reduce their carbon footprints, businesses must learn how to measure progress towards achieving sustainability goals by reducing their scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions. For instance, oil and gas companies and on-site manufacturing processes such as cement production are responsible for up to 90% of GHG emissions through scope 1, 2 and 3. After evaluating the nature and extent of emissions generated, businesses can work on adapting to one or a mix of several decarbonisation pathways to overcome the climate-linked corporate risks.

Pathways for decarbonisation

Companies that are looking to decarbonise their operations have various pathways at their disposal:

1. Energy Efficiency and Storage: Upgrading equipment and technologies, optimising transportation logistics, and improving building insulation are important for improving energy efficiency. Hence, it is important to invest in energy storage technologies such as batteries or thermal storage systems to store renewable energy for use when demand is high. This method is best suited for bringing down scope 1 emissions since it is possible for businesses to increase their energy efficiency by installing energy star-certified appliances or upgrading the HVAC (heating, ventilation and air conditioning).

2. Electrification: In recent years, there has been a strong push from the government to electrify operations by switching to electric vehicles, equipment, and appliances which would lead to reduction in dependence of fossil fuels. The adoption of Electric Vehicles (EVs) is considered to be the cornerstone of decarbonisation policy by replacing the internal combustion engine cars. Popularising the use of EVs would not only decarbonise the transportation sector, but the benefit would also trickle down the supply chains of businesses across industries by reducing emissions emerging from freight.

3. Material circularity or circular economy is a model of production and consumption, which involves repairing, refurbishing, reusing, and recycling existing materials and products as long as possible, thus extending the life cycle of products. In practice, it translates to reducing waste to a minimum. Companies can adopt a circular economy approach to decarbonise operations through non-energy means. Designing products with a longer life cycle can help reduce scope 1, 2 and 3 emissions by bringing down the dependence on raw materials in manufacturing processes.

4. Carbon Offsetting: While transitioning to low-carbon technologies is expensive for businesses irrespective of their size, small businesses in particular find it difficult to access and afford such technologies. Carbon offsetting allows companies to invest in projects that reduce or remove emissions elsewhere. To offset their own emissions, companies can finance reforestation, afforestation, or renewable energy projects among several others.

5. Sustainable Supply Chains: In order to limit the emissions embedded in a product, businesses may want to relook the different components within the supply chain. By finding suppliers with less carbon intensive production processes and lower scope 1 emissions, and by encouraging them to adopt sustainable practices, companies can make considerable progress in their decarbonisation journeys.

6. Low-Carbon Materials: Evidence suggest that using low-carbon or carbon-neutral materials such as sustainable timber, recycled materials, and bio-based materials in production processes positively impacts climate change outcomes. Use of such materials can especially help in reducing scope 1 and 2 emissions of a business.

7. Alternative low or no-carbon fuels such as natural gas, biofuels, advanced diesel and hydrogen (for fuel cells), when used for transportation purposes, can reduce the dependence on fossil fuels. For example, natural gas emits 25% less carbon per unit than petroleum. The Indian government is investing in R&D to explore the potential of green hydrogen as a solution to deep decarbonise energy-intensive sectors such as petroleum refinery, steel, ammonia and heavy-duty trucking.

8. Carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) is a frontier technology that captures, stores, and makes effective use of CO2 emitted during industrial activities. The CO2 can be stored temporarily or permanently in concrete, rocks, and depleted gas and oil fields, which can then be used directly or as feedstock in other chemical or industrial processes and thus help counter scope 1 and 2 emissions.

9. Green Buildings: Constructing and retrofitting buildings with green roofs and walls, energy-efficient heating, ventilation, air-conditioning systems, and passive solar design can bring down energy requirements.

Challenges associated with different decarbonisation pathways

In recent years, technological innovation has led to lower emissions from the power, construction, and transportation sector in a cost-effective manner. However, there are many barriers to decarbonisation in India. Sectors such as iron and steel, cement, lime, mining, fertilizers, petroleum refinery, ammonia and ethylene require high energy and contribute to 25% of CO2 emissions. Some of these bottlenecks in abating CO2 emissions are:

Renewable heat generation is not as efficient: Industrial processes require intense heat which, at scale, can only be generated by burning coal and fossil fuels. The current state of technology does not allow us to generate such heat using renewable energy unless large sums on money is invested in restructuring the furnaces.

Retrofitting expensive solutions for long-lifetime industries: Production facilities have long lifetimes exceeding 50 years, and existing facilities require carbon-free retrofits that are expensive. Long expected lifetimes of machineries means that companies did not budget for the replacement or retrofitting of the assets.

Cost of manufacture is increasing: Companies lose market foothold if expensive adaptation to low-carbon processes increases the cost of manufacture and eventually the price of the commodity rises. It is thus important to reduce the cost of carbon removal without passing on the cost to the end consumer.

Huge decarbonisation investment needed: For a country like India with its GHG emissions taking an upward slope, the transition to low-carbon economy requires upfront investment up to the tune of $2.5 trillion to overcome operational inefficiency in manufacturing and processing units/systems.

Lack of sectoral expertise in climate action: Another challenge that Indian businesses encounter is the inability to assess the impact of specific industrial measures and their financial implications on the business. In fact, small and medium-sized enterprises face a lack of support from supply chain partners and uncertainty in return on investments.

Overall, the lack of material and non-material resources impedes the path of emission reduction among the energy-intensive industries; thereby, slowing the process of mitigation and sequestration of carbon emissions. Changes in government policies and regulations compound the problems.

Whom should companies resort to for decarbonisation?

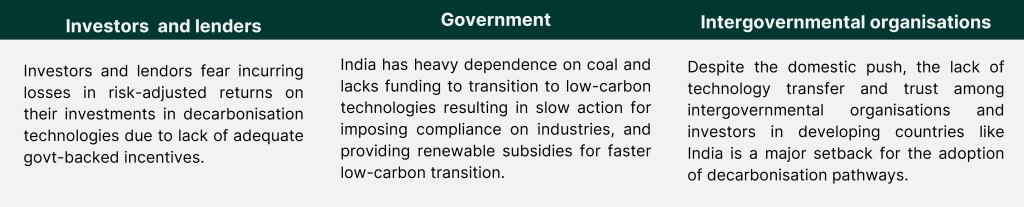

Stakeholder collaboration in the domestic as well as the international market can facilitate the decarbonisation journeys of developing nations.

1. International arena: Industries in regions with well-established emissions trading system (ETS) such as the EU and China have witnessed a decrease in energy consumption and emission – the ETS prompted industries to adopt advanced technologies that support low-carbon operations and output. China also initiated a reward and penalty mechanism to improve its energy efficiency and material circularity to reduce the demand for carbon-intensive products. Similarly, a hydrogen-based economy has made its way through the national commitments of countries like Japan, France and Singapore. However, in comparison to its ambitious goals, the decarbonisation opportunities in the Indian market are moving at a slower pace. India can look to these nations for technology transfers to enable its green transition.

2. Government: Democratising access to clean energy is thwarted by critical gaps such as lack of technology transfers, inadequate flow of capital, and inefficient resource utilisation. With strategic policy approaches such as Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of (Hybrid &) Electric Vehicles (FAME) and public-private collaboration, India has been able to reduce the price of renewable energy and EVs. However, these initiatives need to be scaled up for their impact to be visible.

3. Investors: Low-carbon technologies that facilitate decarbonisation are often capital-intensive. While Indian industries are becoming increasingly climate conscious, limited market mechanisms for pricing carbon emissions hinder them from revamping their existing carbon-emitting assets such as manufacturing and processing machinery. Even debt financiers, especially banks, do not consider low-carbon industrial equipment as an attractive lending proposition. This is where investors and lenders play a stewardship role in making finances available to support their investees to make a green transition.

Carbon markets as an alternative pathway

Carbon markets have two key typologies: voluntary markets and compliance markets that can facilitate decarbonisation.

Voluntary markets: Voluntary markets are based on self-action and are not as strongly regulated. In voluntary markets, trade is not limited to carbon credits – participants can create and trade carbon offsets as well. Demand in the voluntary market is driven by company-level voluntary obligations to demonstrate low-carbon and sustainability-related actions to shareholders and stakeholders. Approval and verification of credits in the voluntary market is done by private companies called registries that have built a brand for themselves for this critical task in the value chain.

Compliance markets: In the compliance market, credits are “generated” by the government. Carbon credits represent the right to release emissions and not emission reduction. Carbon Credits or Allowances are traded in this market. The compliance market implies that the demand for emission reduction is driven by regulation. Approval and verification of emission reduction credits in the compliance market are driven by an extensive regulatory architecture that approves projects based on certain pre-determined conditions.

The 2022 amendment to the Energy Conservation Act permits the creation of a ‘voluntary’ carbon credit market in India where carbon credits can be sold to industrial and individual buyers including. However, domestic carbon markets alone have limited potential to create large-scale shifts unless it is mainstreamed by allowing the participation of sources of international finance, investors, and other similar international ETS.

A transition to a low-carbon economy requires collaborative efforts among governments, industries, investors, and households along with significant investment in R&D to envisage breakthrough greener technologies by 2030. More than 80% of the cumulative emissions can be abated if these key stakeholders accelerate climate action.