There’s a widespread recognition of the idea that managing waste properly is essential for building sustainable and livable cities, yet waste management remains a challenge for many developing countries. Effective waste management is expensive, often comprising 20%–50% of municipal budgets. The consensus to resolve this issue only grows considering the implications that waste has on the environment – the sector accounts for approximately 4% of India’s total GHG emissions. Whilst the aggregate contribution may be insignificant when compared to other emission intensive sectors such as land use or steel manufacturing, waste sector emissions have risen at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 2% during 2005-2018. In the past decade, India’s outlook towards garbage has sharply evolved, both in policy and in practice.

India’s waste management problem is riddled with complexities and continues to grow with rapid economic development and population expansion. Although India does relatively well on maintaining low per capita municipal solid waste (MSW) at 0.39kg/person compared to the global average of 0.74 kg per person, globally it is among the largest producers of waste in absolute terms. India currently generates 62 million tons of waste every year (including recyclable and non–recyclable waste). Of the 1.45 lakh tons of MSW generated per day, only 23% is being processed or treated, while the 72% is sent to landfills. Though waste generation in itself is a problem that demands attention, the lack of a sophisticated waste management system that methodically addresses segregation and treatment of waste is the crux of the issue. Through the lens of environmental justice, poor waste management comes at a social cost – waste often creates a vicious cycle of poor environment, ill health, and poor finances. Those residing in neighbourhoods close to landfills are at a higher risk of health concerns as toxins seep into water sources and the sites become breeding grounds for mosquitoes and flies – leaving residents vulnerable to catching diseases. Fumes from the dumps lead to respiratory ailments as well.

Types of waste

1. Municipal solid waste: Commonly known as garbage or trash, municipal solid waste (MSW) is an umbrella term used for various kinds of waste material including organic wastes such as paper, cardboard, food, yard trimmings, and plastics, and inorganic wastes such as metal and glass. Municipal waste includes waste generated in a dry or wet form by way of domestic and commercial use in municipalities or notified areas. It excludes industrial hazardous wastes but includes treated bio-medical wastes. According to a report published by the Swachh Bharat Mission (Urban), urban India generates 1.45 lakh tons of municipal solid waste (MSW) every day.

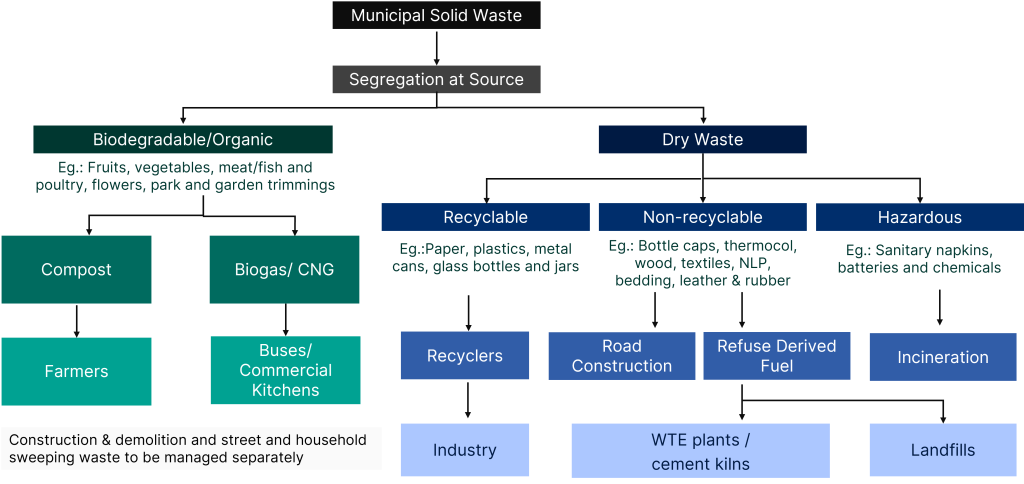

MSW thus refers to various types of waste, including plastic waste, electronic waste (e-waste), biomedical waste, construction and demolition waste, and hazardous waste. The image below illustrates the types of materials that constitute different kinds of MSW and their subsequent treatment.

2. Municipal liquid waste: Water that has been used once and is no longer fit for human consumption or any other use, is considered to be liquid waste. Wastewater can be categorised as industrial and domestic – industrial wastewater is generated by manufacturing processes and is difficult to treat. Domestic wastewater includes water discharged from homes, commercial complexes, hotels, and educational institutions. A byproduct treated wastewater is municipal sludge (a type of MSW), which in India is currently being treated in an unscientific manner without adequate regulatory standards. This leads to indiscriminate sludge disposal on land and in water bodies. Information around liquid waste is largely unavailable in the public domain and the policy apparatus is in a nascent phase – for this reason the article largely focuses on solid waste management in India.

It is important to note that waste management is viewed as a primarily urban issue in India due to the high density of waste generation in urban regions. Additionally, given that rural areas lack the requisite waste management and disposal systems, the scope to estimate the volume of waste generated and resulting emissions is limited.

How does India manage its Municipal Solid Waste?

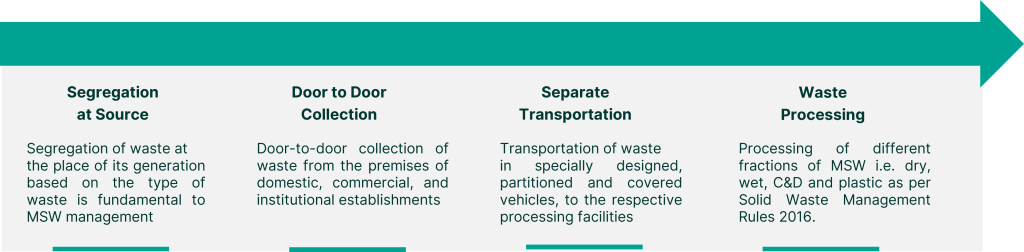

In India, waste management falls under the purview of the Ministry of Environment, Forests and Climate Change, however it is the Urban Local Bodies and municipalities that are tasked to formulate and execute regional waste management systems. The ministry itself has built various missions and regulations that create a framework to facilitate a complex value chain which includes waste collection, disposal, dumping, transportation, recycling, and treatment, as well as avoidance and reduction in the volume of waste generated. The Swachh Bharat Mission 2.0 guidelines released in 2021 provide a comprehensive framework for the flow of MSW management. The solid waste management system demands a stepwise handling of waste materials.

The process begins with segregation of waste at the place of its generation under the following categories:

- Biodegradable wastes (wet waste – food waste, fruits & vegetables and parts thereof, meats, etc.)

- Non-biodegradable wastes (dry waste – plastics, paper, cardboard, rags, glass, metal, wood and inert waste, etc.)

- Sanitary waste and disposables thereof

- Domestic hazardous wastes (such as aerosol cans, paint material, discarded medical supplies etc.)

- Construction & Demolition waste

- Generators of E-waste (including fluorescent and mercury containing bulbs & lamps) shall not mix e-waste with any other waste but deposit the same at the designated e-waste collection centres.

The waste is then supposed to be collected through a door-to-door collection process, generally undertaken by parties subcontracted by the government. Different categories are then processed differently, as per the Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016. This process of MSW management is applicable only to small waste generators such as single-family units or small buildings. Bulk waste generators (BWG) include any entity that generates more than 100kg of solid waste a day. Offices, commercial establishments, large apartment complexes, colleges, school, hospitals, state and central government institutes all fall under the BWG category and are responsible for segregating and handing over their waste.

Why does the issue persist?

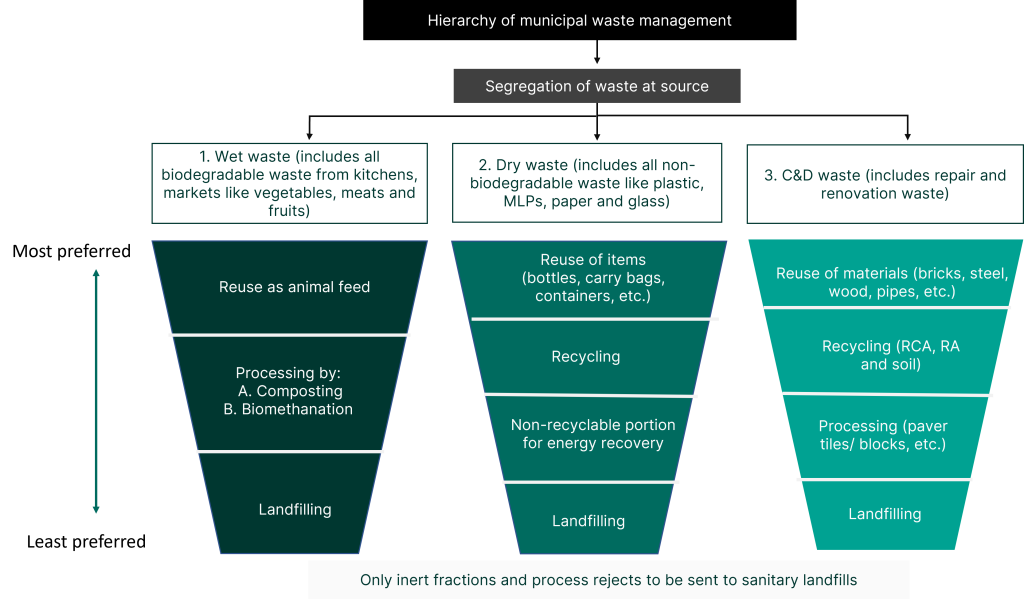

Segregation of waste at source assumes a pivotal role in the entire MSW management process, and this is precisely where the Indian MSW system falls short. Appropriate treatment of waste necessitates segregation of waste at source, which at present is largely done by waste collectors and contractors instead of the waste generators. Due to this, the responsibility to segregate gets shifted down the chain to contractors who are paid by the weight that they dump into landfills and thus have little incentive to meticulously segregate waste and scourge for recyclables. This gives contractors a perverse incentive to indulge in practices that go against the guidelines on hierarchy of municipal waste management (figure 3) provided by Swachh Bharat Mission 2.0 that recognises landfills as the last resort for waste disposal.

With their revenue being proportional to the waste dumped, these contractors are incentivised to dump more, resulting in existing landfills receiving an unmanageable amount of waste. Furthermore, the only way in which segregators can benefit from segregating plastic is if they sell the product at market value to recyclers – there is thus little incentive for segregators and producers to focus on recycling. A lack of comprehensive methods for plastic waste management, limited collection and recycling of single use plastic, and unscientific methods of recycling by the informal sector pose some of the key challenges in this area.

So while on paper the MSW value chain is comprehensive, with provisions for appropriate treatment existing for all kinds of waste – collected waste ultimately ends up in landfills that pollute groundwater and release methane. These landfills are susceptible to fires, putting communities in surrounding neighbourhoods at risk.

What is being done to resolve the waste problem?

Resolving the MSW conundrum requires navigating through the functions of multiple stakeholders in the value chain, which adds to the complexity in reaching systematic solutions. In this regard there has been an active effort by the government to develop a robust policy landscape around waste management in India.

Multiple sets of rules and guidelines streamline waste management in the country. These include:

- Solid Waste Management Rules (SWM), 2016

- Plastic Waste Management Rules, 2016 and 2018

- Biomedical Waste Management Rules, 2016

- Hazardous and Other waste (Management and transboundary movement) Rules, 2016

- Construction and demolition guidelines, 2016

- National Resource Efficiency Policy (NREP), 2019

- Waste to Wealth Mission

- Swachh Bharat Mission – Urban

- E-Waste (Management Rules), 2022

- GOBARdhan

These rules set a modus operandi for all stakeholders in the value chain, including domestic waste generators and commercial waste generators, waste collectors, as well as waste processors. NREP, 2019 stands out among the list of policies as a forward-thinking framework prepared to create a facilitative and regulatory environment to mainstream resource efficiency across all sectors with ‘waste minimisation’ as its guiding principle.

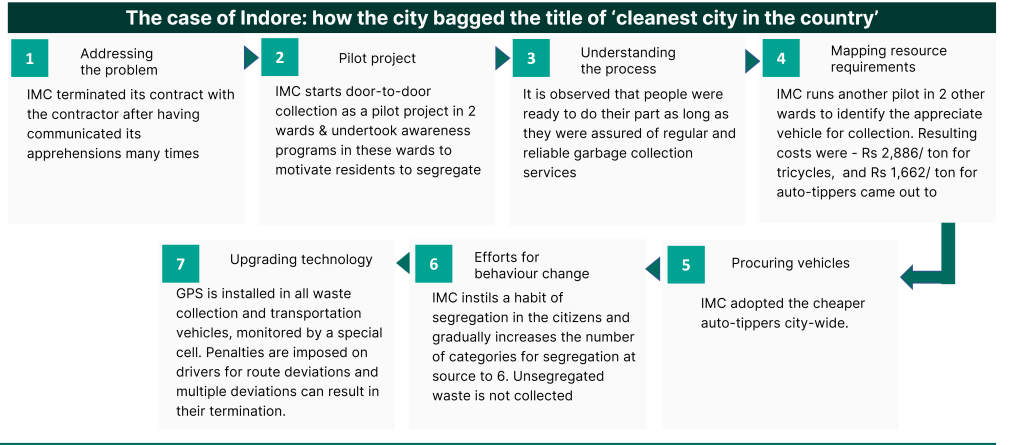

Through Swachh Bharat Mission – Urban, the government has been vocalising its resolve to achieve the sustainable development goals associated with sanitation, cleanliness, and hygiene. There is also an explicit recognition of the impact that waste management has on the environment. The mission addresses the need for a much-needed decentralised approach to waste management. Since the manner in which different cities generate and manage waste varies greatly, treatment and processing of waste must depend on the type and volume of waste generated. Ensuring scientific segregation of waste at source, processing waste in segregated fractions, recovering resourcing and ensuring recycling to the maximum extent can potentially minimise landfilling to 20% of less. To execute its vision of decentralised waste management, the SBM 2.0 guidelines mandates Urban Local Bodies to come up with a City Solid Waste Action Plan (CSWAP) for their respective regions. Cities have been given targets to duly remediate the legacy dumpsites. Further, cities with nonconforming air quality have been asked to replace the common manual street sweeping with air quality friendly mechanical sweeping and process the construction and demolition waste as per the Construction and Demolition guidelines, 2016. The CSWAP must capture the gaps in dumpsite remediation, mechanical sweeping, and construction and demolition waste processing facilities. Swachh Survekshan – India’s benchmarking and ranking tool – has been evolved to capture the measures that a city takes towards source segregation, material reprocessing, and zero-landfills.

However, unlike other focal areas of the mission, each year the size of the problem pertaining to MSW continues to grow. Increase in consumption, population expansion, and rapid urbanisation leading to record volumes of waste generation call for systemic reforms that are difficult to implement and behavioural reforms that are slow to come.

GOBARdhan was launched by the central government in April 2018 as a part of the Swachh Bharat Mission-Gramin. The scheme aims to better biodegradable waste management and positively impact village cleanliness and generate wealth and energy from cattle and organic waste.

The waste to wealth mission aims to create an enabling environment for the growth of a circular economy. Circular Economy is a model of production and consumption, which involves repairing, refurbishing, reusing, and recycling existing materials and products as long as possible, thus extending the life cycle of products. In practice, it translates to reducing waste to a minimum. Circular economy promotes resource optimisation and recovery of waste by recycling or repairing, with the intent to reduce raw material consumption.

Gaps in the policy apparatus

Despite the flow of MSW management being heavily dependent on segregation of waste, non-segregation is not penalised under government policies such as the Solid Waste Management Rules, 2016. The existing policies try to address the waste cycle from – from generation to disposal – but the apparatus demands a relook to explore innovative mechanisms, specifically on the following aspects:

1. No incentives to encourage recycled products/alternatives: At present industries have no incentive to recycle or invest in research and development that would enable them to come up with circular alternatives. Currently the recycled products and alternatives fall under the same GST brackets as the products made from virgin materials thus there is no provision to encourage use of recycled products/ alternatives.

2. Policy for Marine Plastic: The growing marine plastic concern in India requires more focus yet currently there is no policy, rule or guideline which caters to marine plastic waste entering water bodies.

3. Policy for Mainstreaming of the informal sector: Even though the informal sector plays a significant role in making dry waste value chain resource efficient and circular, yet there is no policy mandating the mainstreaming of the informal sector.

4. Extended Producer Responsibility limited to plastic and e-waste: At present EPR framework is limited to only plastic and electronic waste and yet to be fully effective. Lack of EPR framework for other dry waste streams such as textile, paper, tyres/rubber, metal and glass etc. leads to unscientific disposal of these waste streams while also losing valuable resources.

5. Inadequate Labelling: Inadequate labelling on products makes it difficult to segregate and categorise products. Products with low recyclability if mixed with products with better recyclability can cause lesser recovery and sub-standard recycled products.

6. Landfilling of recyclables: Currently there is no provision mandating ban on disposal of recyclables in landfills. Disposing of recyclables in landfills/dumpsites not only leads to loss of valued resources but also causes environment pollution.

Overall lax implementation and gaps in policy appear to be a huge barrier in effective waste management. As the volume of waste being generated goes up, the existing waste management infrastructure struggles to grapple with the magnitude of the issue. The implications that follow are multifold, and demand urgent action. Non-biodegradable and toxic wastes like radioactive remnants can potentially cause irreparable damage to the environment and human health unless they are disposed off strategically.

Implications on Climate

As waste decays in landfills, it generates high levels of CO2 and methane. Accounted over a hundred years, methane has a global warming potential that is 28 times higher than CO2. With almost 15,000 MT of garbage remaining exposed in the country each day, waste has also become a significant reason for rising pollution levels. More than a quarter of methane emissions (26%) in the metropolitan city of Mumbai originated in landfills. For the national capital Delhi, landfills accounted for 6% of methane emissions. As population levels climb, methane emissions are expected to rise dramatically – with solid waste landfills being major contributors. Furthermore, waste dumped in landfills is periodically burnt to create space for new waste, heightening air pollution levels. To exacerbate woes, when water filters through open landfills, waste breaks down to form a highly toxic liquid called leachate, which then pollutes ground water and waterways.

Understanding waste management from the climate perspective is critical on two accounts – firstly, the environmental implications of poor waste management simply cannot be ignored, and secondly, addressing the causal effect of waste on climate change helps bring waste management into the broader policy discourse.