In the previous articles in our series on CBAM, we covered EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism and its potential impact on the Indian industry. This article will focus on how industries can prepare for the CBAM and its impacts as we come closer to the implementation of the transitional phase in October 2023. From an Indian perspective, the iron & steel, and cement industries – each one strategic to India’s trade with the EU – are particularly vulnerable to CBAM’s impact. However, there are ways in which businesses can reduce these vulnerabilities.

Why should you be concerned about CBAM?

The race to reach net-zero gained momentum in recent years and EU’s CBAM is an attempt to mobilise the market to find sustainable production alternatives as they look to maintain their leadership on the net-zero drive. This move though comes with its own set of potential political implications – not the least of them being that other countries may engage in similar protectionism and penalise carbon-intensive processes as a form of economic tit-for-tat. It’s not just countries that are on the net-zero path, as companies are setting their own net-zero targets. There has been a concerted push from private enterprises where we are witnessing a rise in voluntary measures to limit and reduce carbon emissions. Out of the 4567 companies that have put in place such targets, 65 are Indian engaged in sectors such as automobiles, construction, mining electric utilities, textiles, and chemicals among others. There is also a growing acceptance of Internal Carbon Pricing among Indian businesses. As a result, despite governments and businesses criticising EU’s policies, many of them are already examining their supply chains and adapting to low carbon pathways. With CBAM’s added impetus, to stay competitive, businesses, especially those under the initial scope of CBAM (iron, steel, cement, electricity, fertilizers, aluminium, and hydrogen), will need to move quickly to adopt best practices and reduce emission intensity.

The impact of CBAM is complex

The implementation of CBAM will result in varying degrees of impact on producers, importers, and end users. For example, steel production, which is a particularly emission intensive production process in India, may be subject to a 12.6% duty. In contrast, fertiliser production is relatively less emission intensive due to which levies on fertilizers are likely to be around 4.6%. The complexity in complying to CBAM is exacerbated when the product being traded is a finished good. To break this down, let us take the example of a car exported to EU – consisting of several components made of aluminium, iron, and steel. Each component would have varying degrees of embedded emissions, meaning, varying levies for every such component. So while the average duty on steel under CBAM may be 12.6%, this number will vary for different components in the car that have been manufactured from steel. This makes calculation of CBAM a mammoth task. The regime is complex and the onus to assess production processes and identify exposure lies on the businesses.

Conditional Exemption to CBAM: can your business benefit?

In its provisional agreement, the EU has iterated that conditional exemptions from CBAM will be limited to countries that already have some sort of Emissions Trading System of Carbon Pricing in place. The good news for Indian business is that the Indian government is working on developing a domestic ETS which is expected to come into place in by Q4 2023-24. The structure and framework of the Indian ETS are being worked out and until such a system is fully in place, businesses cannot benefit from any corresponding CBAM exemptions. There is of course the existing Perform Achieve and Trade Scheme introduced in 2012, that could act as an implicit carbon pricing mechanism. The scheme incentivises energy incentive industry to reduce their consumptions, but whether this will be considered by the European commission for exemption from CBAM is unclear at present. Given the uncertainty surrounding the exemptions and the route to availing them, businesses would do well to make their own plans and focus on two aspects: finding ways to reduce emissions and calculating embedded emissions well.

A three-step approach: Identify, Calculate, and Reduce

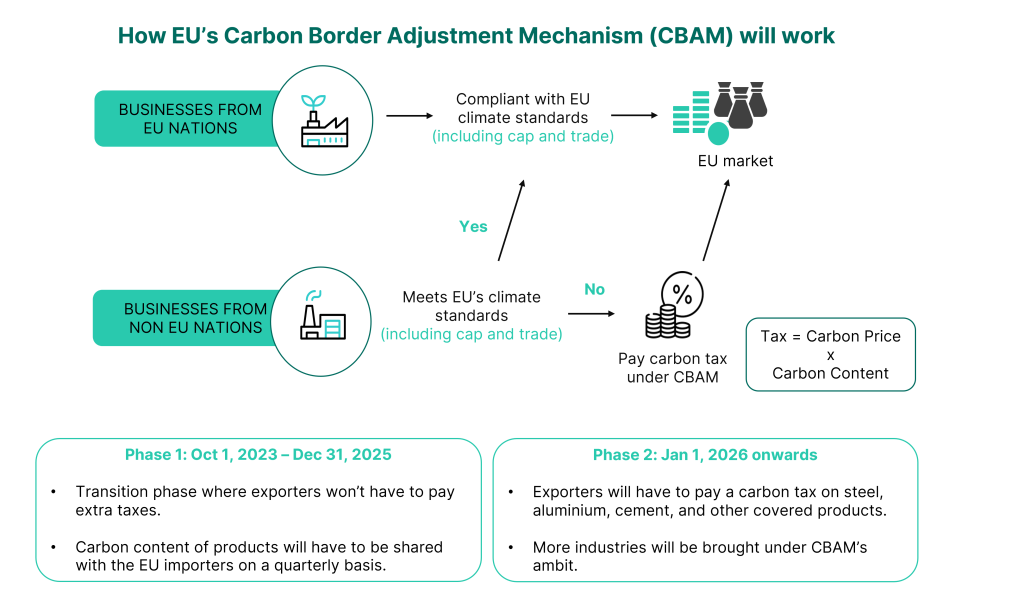

How CBAM will affect your business is contingent on a multitude of factors. Some of them are dynamic and will be known once implementation begins. What we do know is that a carbon tax will be levied based on the amount of carbon emissions resulting from the production of the product in question.

Identify: According to the provisional agreement, the scope of the regime is limited to a few emission-intensive industries (iron, steel, cement, electricity, fertilizers, aluminium, and hydrogen) during the transitional phase of CBAM (October 2023 – October 2026). The European Commission has released a list of products on which CBAM would be applicable during this period. Businesses must identify which of their products are liable under the ramifications and prioritise the calculation and reduction of emissions embedded in exposed products.

Calculate: Proposed Regulation of the CBAM provides rules for general calculation of embedded emissions in a product, but these rules lack specifics. More detailed formulae for calculation of emissions under CBAM can be expected closer to the date of implementation of the regime. These specific formulae are expected to account for production processes, emission factors, installation-specific values of actual emissions and calculation methods for indirect emissions. What we do know is that countries or businesses that are unable to credibly calculate embedded emissions will be levied duty as per default values. These default values will most likely be extremely conservative in nature and will assume a higher amount of embedded emissions than what the actual emissions may be. Goes without saying that the higher the embedded emissions, the higher the number of CBAM certificates that will need to be purchased and surrendered and hence, the higher the cost borne by the exporter. The ability to execute accurate and credible calculations is all the more important for those businesses that have relatively cleaner production processes – to help them avoid punitive default values. Companies must look to immediately start establishing internal monitoring systems that allow them to quantify embedded emissions in line with CBAM guidelines.

Reduce: As discussed in our previous article on CBAM, the mechanism clearly intends to prompt reduction in emissions by disincentivising emission-intensive supply chains. In this regard, reducing emissions as efficiently as possible is non-negotiable. Possible ways to reduce emissions are:

1. Reduce your direct emissions: For the transitional period, CBAM is applicable only to scope 1 emissions (emissions associated with fuel combustion in boilers, furnaces, vehicles) embedded in the product. Investing in greener technology that reduces Scope 1 emission intensity such as alternative fuel sources (biofuel, waste to energy) and more energy efficient equipment to bring down the embedded emissions almost immediately.

2. Assess your supply chain: It may also be in your business’ interest to rethink sourcing. Find suppliers with less carbon intensive production processes with lower scope 1 emissions. This reduces the emission intensity across the value chain and hence reduces the potential impact of CBAM.

Once the transitional period is over, CBAM will be applicable to emissions across the value chain. It may be prudent for businesses to look for cleaner energy sources and reduce scope 2 emissions (bought energy, such as electricity, steam, heat, and cooling) sooner rather than later given that these interventions have a relatively long gestation period.

Another short-term solution is to restructure export destinations. Until technical or strategic solutions to reduce emissions are achieved, business may want to sell products with lower embedded emissions to EU based importers and sell emission intensive products to countries that do not have an ETS or carbon pricing mechanism. Export reshuffling can only be a transitioning strategy as countries and companies put greater impetus on achieving their own net-zero targets. Consumers too, are becoming increasingly aware of the importance of making sustainable choices. In this context, reducing emissions not only prevents businesses from falling to punitive measures but can potentially provide a competitive edge. Some Indian companies have voluntarily established internal carbon pricing to reduce emissions and encourage innovation in the field of a low-carbon economy. These companies may benefit from exemptions under CBAM. The government too is working to cushion the industries from impact by working on its own Carbon Credit Trading Scheme. This could help counter the impact of a carbon border tax. While the details of such a scheme are not yet known, the industry can expect developments in the coming months.

Key Takeaways:

EU’s CBAM is a complex mechanism that enforces climate commitments across the supply chain. As India awaits the introduction of its own ETS, industries remain vulnerable to duties that inflate cost of products and diminish the competitive edge. A three-step approach to potentially limit the impact of CBAM on your business is:

- Identify which of the products fall under the scope of CBAM to examine how exposed your business is to ramifications under CBAM.

- Once identified, work towards reducing embedded emissions in the products by opting for low-carbon materials or investing in greener technology.

- Lastly, set up a robust monitoring system to effectively calculate emissions embedded in your products to avoid repercussions of punitive measures under CBAM.