India’s current policy and regulatory landscape for waste management provides a forward-thinking, actionable framework with scientific waste management as the guiding principle. In our previous article we discussed the importance of transforming science-based policy into praxis as the country moves further up its growth trajectory and consumer patterns evolve, leading to more waste being generated than ever before.

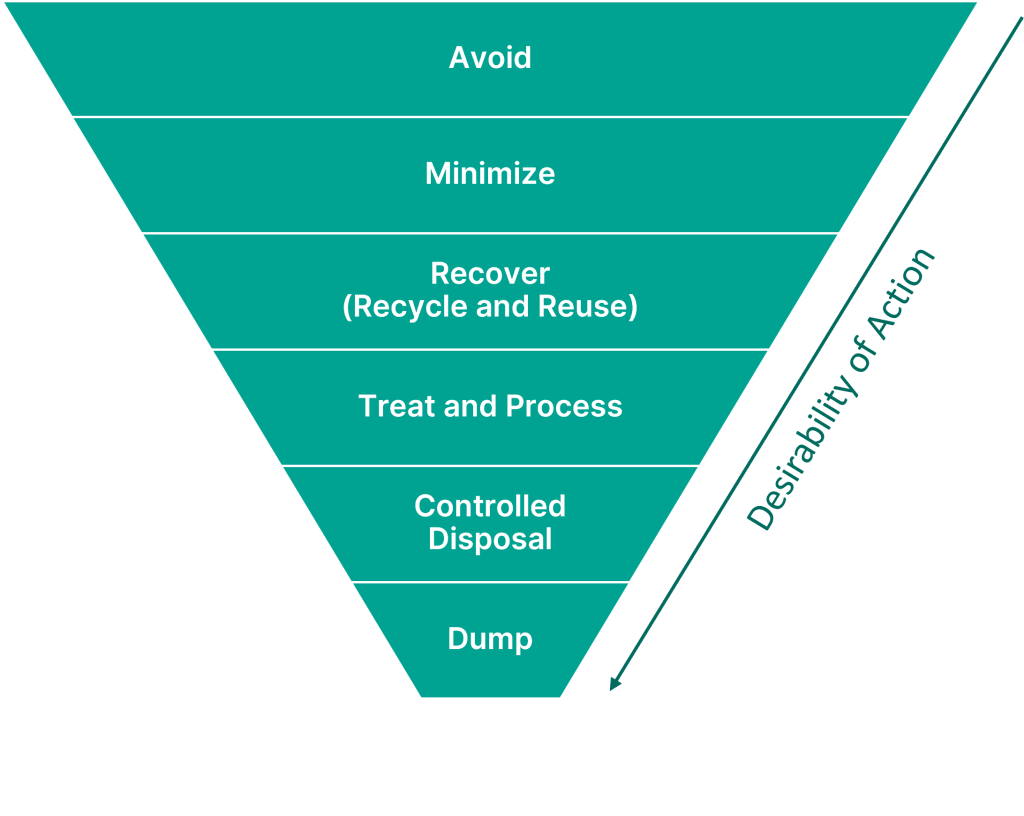

In the wake of the economic growth and unprecedented rate of urbanisation, India has witnessed a six-fold rise in annual material consumption between 1970 and 2015, from 1.18 billion to 7 billion tons. This number is expected to double to about 14.2 billion tons by 2030. Ideally, the solution to the waste problem begins with avoiding or reducing consumption as much as possible, recovering material by repurposing, reusing, or recycling and only then letting the waste reach the treatment and processing stage, with disposal being the last resort.

But waste also has potential – and with economic prosperity, the ability to utilise waste by adopting a circular economy approach has advanced. Dry waste in particular is the most valuable stream of waste among all municipal solid waste (MSW), owing to the high economic value of dry recyclables. Further, dry waste makes up approximately 35% of the 0.14 million tons of MSW generated each day, making it all the more important for the government and industry to tap into its potential.

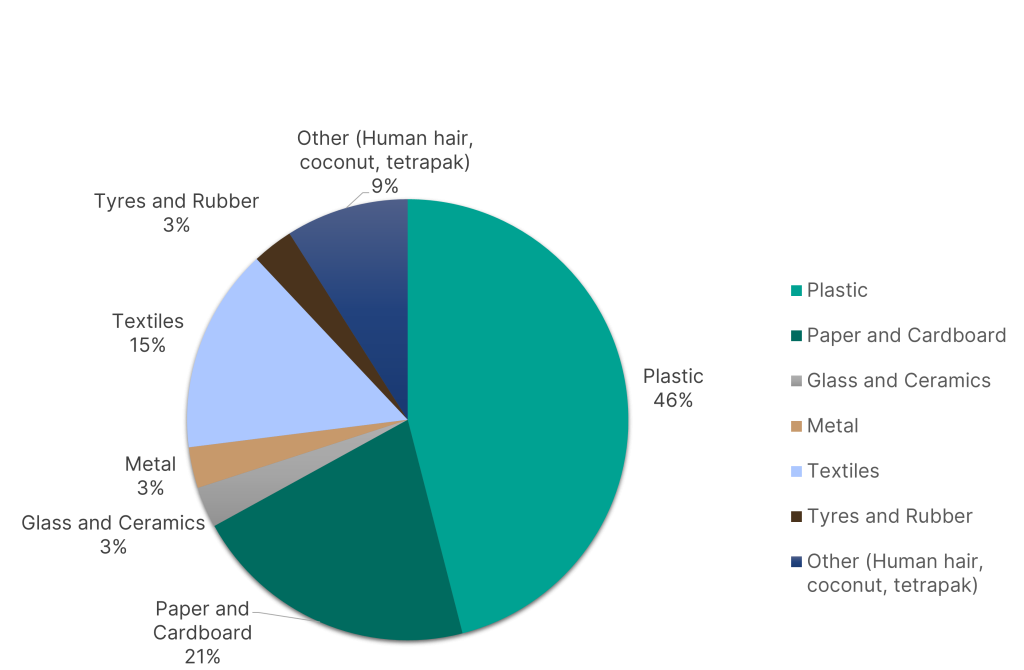

Of the total dry waste generated, 20-30% is either recyclable or resource recoverable, meaning the waste can serve some function by way of repurposing or recycling. To effectively tap into the recovery potential that dry waste holds, it is important that we manage all components of dry waste scientifically. At present plastic constitutes nearly half of all dry waste generated, followed by paper and cardboard, textiles, and other materials as shown in the chart below:

Though the recovery potential of dry waste is immense, efficiently managing dry waste in an economically and environmentally beneficial manner poses several operational challenges and requires investment of significant resources.

Challenges to plastic waste management

Out of dry waste components shown above, plastic is the most major component. India generates approximately 15 million tonnes per annum of plastic waste, and out of this approximately 60% is recycled whereas the rest is left uncollected or littered. Through recycling, waste is most often converted into lower quality products such as granules, pellets, or flakes—which at best delays plastic from seeping into soil, oceans and the food system. Although plastic recycling in India is almost 3 times the global average, there are no comprehensive methods in place for plastic waste management. In 2018, India’s per capita plastic consumption was 11 kg, much below the global average of 28 kg and close to 10% of per capita consumption in the US. By 2031, plastic waste generation in India is expected to grow by more than 3 times from current levels.

An up-and-coming alternative to traditional plastic is bioplastics, which is made wholly or in part from renewable biomass sources such as sugarcane and corn, or from microbes such as yeast. However, bioplastics come with their own set of risks and limitations:

- GHG emissions from processing bio-feedstock into plastics is significant.

- Not all bioplastics are biodegradable – some are chemically identical to fossil-fuel based plastic.

- If not identified and collected separately, bioplastics may getting mixed with recyclable plastics which makes the processing difficult.

- Recycling and recovery infrastructure needs modifications to process bioplastics.

Challenges in Other Dry Waste Components

Tetra Pak Processing: Commonly used compound packaging such as Tetra Pak comprises three recyclable components i.e. 75% paper, 20% polyethylene and 5% aluminium thereby making its recycling difficult and cost intensive.

Unscientific segregation and recycling: Segregation of metals from other waste streams is carried out by untrained informal sector workers. Small metal scraps are lost due to unscientific waste collection resulting in loss of valuable metal resources.

Issues in recycling glass and ceramic waste: Recyclers and handlers find the glass and ceramics handling unattractive due to risks of injuries and breakages. There is no mechanism of communication between cities and the glass recycling industry

Segregation and processing of textile waste: The industry has a recycling potential of 50%, at present only 25% is being recycled/reused. Circular (reuse & refurbish) barter system exists in small towns, there is a limited collection and recycling system for textiles.

Processing of tyres and rubber: The Indian automobile sector is growing, and with it, the demand for tyres, but currently there is no tracking of discarded tyres and monitoring of their disposal across India. Despite retreading of tyres by the unorganised sector, a large portion of the scrap tyres are dumped in landfills.

Localised processing facilities for Thermocol: Thermocol is widely used in packaging of goods and is technically a recyclable material. But transportation of thermocol is a challenge due to its ultra-low density and high volume resulting in limited processing/recycling.

Other dry waste: Due to increased demand for recycling in recent years, coconut shells are being segregated and shredded by informal workers. But in smaller and remote cities segregation, transportation and logistics cost of coconut waste act as significant barriers for coconut recycling. Another area that lacks scientific management is human hair waste despite there being a large-scale economy running around human hair. The collection system is often limited to large generators of hair waste like large temple complexes, whereas small units generating hair waste such as salons, beauty parlours, etc. are not connected to the collection system. The efficient and environmentally safe utilisation of human hair also requires appropriate technologies for different uses of hair waste.

The Solution? Building and maintaining a robust circular economy

As is evident, the magnitude of the waste management problem is huge, and significant strides need to be made by all sets of stakeholders to counter the issue. Mindful consumption along with scientific segregation and disposal of waste are important steps that can help deaccelerate the problem, but these changes are slow to come even when supported by policy and action. The planet is on a carbon budget – which means more innovative and actionable approaches must be adopted.

One key approach that is gaining momentum is circularity or circular economy – a model of production and consumption, which involves repairing, refurbishing, reusing, and recycling existing materials and products as long as possible, thus extending the life cycle of products. In practice, it translates to reducing waste to a minimum. Circular economy promotes resource optimisation and recovery of waste by recycling or repairing, with the intent to reduce raw material consumption. Recycling is a crucial part of the circular economy, but the goal of “true recycling” is to convert the waste resource back to its original form, without sacrificing the quality or integrity of the material in the process.

A circular economy also makes fiscal sense. Material recycling facilities (MRF) have the potential to play a significant role in making dry waste management circular and also adding value to the economy. If implemented, MRF can potentially generate employment of 40 Lakh person-days during construction of MRFs and ~80 Lakh person-days in perpetuity for operations & maintenance of these facilities. The recovery of waste has immense potential to feed into the economy – dry waste recycling has a potential to generate approximately $1.4 billion, compost and bio-CNG from wet waste can generate revenues of nearly $40 million and $200 million per annum respectively. Similarly, construction and demolition waste has the potential to generate revenues of approximately $50.5 million per annum.

How can different stakeholders contribute?

As per the Environment Protection Act, 1986, the federal government has the authority to regulate all forms of waste – this task is undertaken by the Ministry of Environment, Forest, and Climate Change. Meanwhile, the authority to enact and enforce new regulations is vested to the individual State Pollution Control Boards (SPCBs). At the ground level, however, it is individual urban local bodies (ULB) that are responsible for preparing and financing waste management plans. These plans must include door-to-door service and the establishment of centres for processing waste, and recycling materials. These public bodies as well as citizens and private entities, all have a role to play in managing waste and maintaining the cities. Here’s how different stakeholders can contribute towards a comprehensive waste management system:

1. Government:

In our previous article we highlighted how existing policies are falling short in creating a positive environment for recycling in the country, and are silent on key issues including marine plastic and incorporation of the informal sector into the waste management system.

Besides the policy gaps, there also exist severe regulatory gaps that the government must bridge in order to prevent leakages in the dry waste management system. Here are some steps that the government must take:

Create a more robust Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) framework

EPR is an approach under which a producer’s responsibility for a product is extended to the post-consumer stage of a product’s life cycle. In India EPR partially shifts the physical and economic responsibility upstream towards the producers and away from the municipality. Ideally EPR should either bind or incentivise producers to take environmental considerations into account when designing products.

The current Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) framework in India is complex and insufficient – the complexity makes it harder for manufacturers to comply and for authorities to implement the framework. The framework is not yet entirely active, and has not been conceptualised for other waste streams like paper, textile, tyres/rubber, metal and glass etc., which leads to unscientific disposal of these waste streams while also losing valuable resources. Furthermore, the present EPR framework does not take into consideration the environment and life cycle impact of the products or recyclability of the materials used, and neither does it discourage the use of multi-layered plastics and single-use plastics that are harmful to the environment. Without EPR no circularity can be obtained, and thus the framework must be fixed and strict compliance must be ensured.

Fill infrastructural gaps

Set up mechanisms for innovative financing: There are very few businesses that incorporate the principles of circularity into their production and operations. This is largely due to the fact that building circular businesses is important – such businesses require financing support at various stages. Many circular businesses slip back and due to a lack of financial support and incentives. Little is being done to identify such businesses and to then extend required support.

Simplify the Registration Processes: Recycling businesses require multiple clearances thus delaying the set-up while the unorganised sector continue to run their businesses without any clearances. To ensure scientific recycling of materials this process must be simplified.

Adopt innovative business models and technology options

Resource recovery, processing, and disposal of municipal solid waste can benefit greatly if judicious technological choices are made. It is important to utilise the resources by employing a combination of technologies suitable for treating various components of dry waste, some of which are Material Recovery Facilities, Mechanical Recycling, Refuse-Derived Fuel (RDF) for Co Processing, Plastic to Road Construction, Pyrolysis etc.

Bring the informal sector into the mainstream

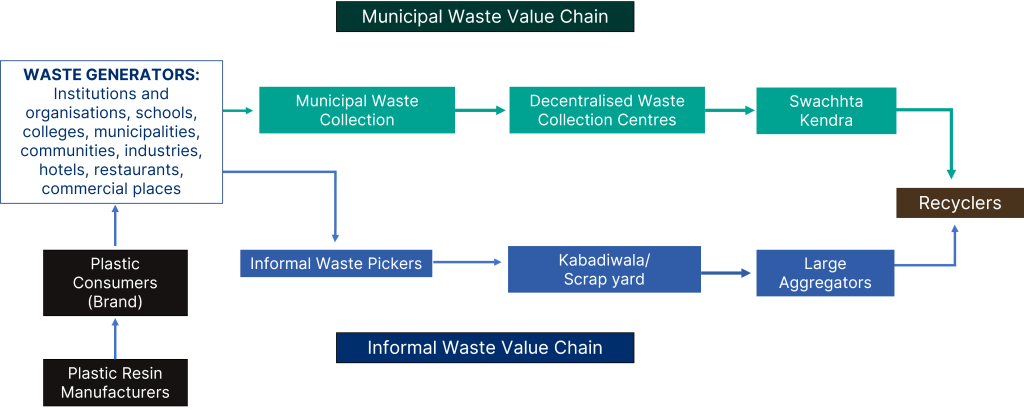

The informal sector plays a major role in making the material flow of the dry waste value chain (as can be seen in the figure below) a resource efficient and circular economy by sorting the dry waste into different components and recovering valuable resources.

Informal waste collectors include individuals, associations, or waste-traders who are involved in sorting, sale and purchase of recyclable materials. Waste pickers are informally engaged in the collection and recovery of reusable and recyclable waste from the source of waste generation and contribute to 70% of all plastic recycled in the country. These collectors then sell the waste to recyclers directly or through intermediaries. Estimates suggest that globally the informal waste economy employs 0.5% – 2% of the urban population worldwide. In absolute terms that would mean between 7-28 million people are employed in India’s informal waste sectors. Despite the sizable number there is a lack of integration of the informal sector into the mainstream recycling industry limits their involvement to only certain fractions of waste. The IWE is thus often ‘unseen’ to those who generate and deposit most of it, while also being plagued with low wages and exposed to significant health risks.

2. Urban Local Bodies:

Constitutionally a great deal of power is vested in local governments. Under SBM 2.0 Urban Local Bodies have been handed the responsibility to develop decentralised waste management systems in the form of CSWAPs that fit the regional and demographic requirements. Implementing and ensuring compliance to the CSWAPs is also a function that ULB’s are required to undertake. The SBM 2.0 guidelines ask cities to ensure segregation of waste at source, process waste in segregated fractions, recover resources and recycle to the maximum extent and minimise landfilling to 20% or less (including reject material coming out of processing). Further, Cities with nonconforming air quality must replace the common manual street sweeping with air quality friendly mechanical sweeping and process the construction and demolition wastes as well. The mission guidelines do a comprehensive job of listing the ULB’s responsibilities towards making cities cleaner and managing waste effectively and efficiently. Under the mission knowledge around technological advancements and strategic recommendation is disseminated regularly, and funds for infrastructural development have been set aside. As elected members of a public body, ULBs make best use of the knowledge as well as resources available and take measures to fulfil their responsibilities. ULB’s must also learn from the example cities like Indore about source segregation, Surat about material processing, and Gangtok about plastic waste management – and come up with robust waste management mechanisms.

3. Private Sector:

By 2025, India’s waste management sector is expected to be worth US$13.62 billion with an annual growth rate of 7.17 percent. Taking cognizance of the state’s limited bandwidth to resolve the waste issue and the size of the opportunity for private entities if they were to enter the waste management space, the union government encourages municipal bodies to partner with the private sector to find solutions. Innovative approaches towards waste management technologies, advancing recycling capabilities, and helping the government build cities with well-thought out waste management systems can benefit the citizens, the state, as well as the private entities.

The union government has launched several initiatives such as Aatmanirbhar Bharat App Innovation Challenge, Atal Innovation Mission (AIM), Startup India Seed Fund Scheme, Startup India Initiative etc. that provide platforms for startups to solve pressing problems, among which are waste management and climate change.

4. Citizens

As iterated above, segregation of waste at source is a critical piece to the puzzle. A sense of ownership towards the surrounding environment and understanding the climate implications of waste can greatly help the waste management system. If citizens fail to change waste management practices at an individual level, the government may opt for a more coercive approach wherein waste collection becomes chargeable and non-compliance follows heavy penalties. This coercive approach is common in several developed countries, but India’s policy apparatus has a behaviour change approach embedded in it.

A circular economy-based development approach is among the key strategies being adopted for achieving the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The economic advantages of this model are also evident in the numbers. For this approach to succeed, it is imperative that all stakeholders strive towards a fundamental change in how they approach manufacturing, consumption, and disposal, and turn towards an outlook that places sustainability at the forefront.