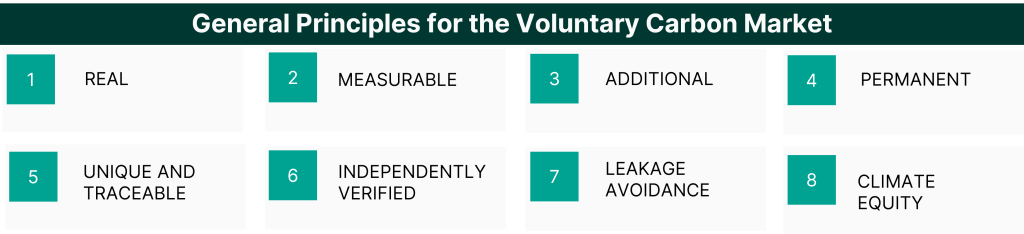

The carbon market is a system that allows the buying and selling of carbon credits and mitigate GHG emissions. By putting a financial value on carbon emissions and fostering a market-driven approach, it aims to accelerate the transition to a low-carbon economy and combat climate change. However, the absence of principles can lead to challenges and inconsistencies within this market. To ensure integrity, transparency, and effectiveness of carbon offset projects, the voluntary carbon market has curated a set of principles that provide a common framework for evaluating and comparing projects, promoting best practices, and ensuring that the offsets generated are robust and credible.

They enable stakeholders to make informed decisions, trust the legitimacy of offset projects, and verify the environmental impact of their actions. The core carbon market principles for determining the quality and credibility of carbon credits have been discussed in the following section.

Principle 1: Real

The principle of “real” ensures that a carbon project in the voluntary carbon market (VCM) generates genuine emission reductions or removals. It requires projects to accurately quantify and verify their environmental impact, ensuring that the claimed reductions are not based on hypothetical or uncertain scenarios. Real projects are based on tangible actions and technologies that lead to measurable emissions reductions or removals, ensuring that the investments made in the voluntary carbon market have a genuine impact in mitigating climate change. To ensure realness, third-party auditors must evaluate the available evidence, carry out field observations and look into the reputation of the project developer before awarding a certificate for the same.

Principle 2: Measurable

This principle emphasises the importance of quantifying and tracking carbon emissions reductions or removals in a transparent and standardised manner. A carbon project must ensure that it follows all relevant standards and protocols pertaining to monitoring, reporting and verification must be adhered to at all times. This ensures that the carbon credits issued are accurately calculated and verified, allowing stakeholders to assess the environmental impact of their investments and make informed decisions about supporting or participating in the project.

Principle 3: Additional

As per this principle, the project/organisation must be able to demonstrate that all emission reduction/ removal achieved is entirely additional i.e. the emissions impact would not have been realised in the absence of the project. For the project to have additionality, project developers must also demonstrate that the project exists by virtue of the funding secured from carbon credits and using financial modelling tools to illustrate how future credit revenues were a decisive factor in pursuing the project. At present protocols such as – Verified Carbon Standard, Gold Standard, American Carbon Registry and the UNFCCC have their own tools for additionality assessment.

Evaluating whether GHG reductions are additional is an exceedingly complex task. For additionality to be perfectly verifiable there is a need to develop protocols and investigate cases on a country-to-country basis- since legal requirements and cost of energy vary across the globe. This may also create problems with the sale and purchase of carbon credits in the international market. Strong additionality determination criteria might lead to developers shifting projects to developing countries and LDCs with- lax legal requirements for managing GHG emissions, to demonstrate additionality.

It is important to note that there is a misconception that leads to emission reduction/removal claims being slotted into the binary of being additional or not – when in reality, determining additionality requires comparison with a hypothetical where there is no revenue from the sale of carbon credits. The hypothetical is prepared using educated predictions but is far from perfect. Recently developed analytical tools such as dynamic baselining, remote sensing and monitoring will hopefully strengthen the credibility of assessments for projects in the future.

Principle 4: Durability/Permanence

Durability refers to the physical longevity and integrity of carbon storage. In the carbon market context, it emphasises the need for carbon offset projects to generate emission reductions or removals that have long-term or permanent effects on reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Durability ensures that the environmental benefits achieved through these projects are sustained over time and not easily reversible. This principle acknowledges the importance of maintaining the integrity of carbon offsets and preventing any unexpected reversals or losses of emission reductions.

To ensure durability, projects must carefully assess and mitigate risks that could compromise the longevity of their emission reductions, such as natural disturbances, changes in land use, or technological obsolescence. By adhering to the principle of durability, the carbon market can provide confidence to stakeholders that their investments in emission reductions will have a lasting positive impact on mitigating climate change. Durability is constrained by both natural and anthropogenic risks of reversal. The price of a carbon credit is greatly impacted by durability, which varies by project type, broadly there can be two types of projects:

1. Short-medium term projects: which result in the biological sequestration of carbon, for example, the forestry credits earned against which command a low price and

2. Long-term projects: which result in the geological sequestration of carbon, for example, the mineralisation credits earned against which command a high price in the VCM.

The benchmark for permanence is generally set at 100 years, but more stringent protocols and registries can demand a longer time frame going up to 1000 years to truly label a carbon offset as permanent.

Principle 5: Unique and Traceable

The test of uniqueness demands that no more than one carbon credit be associated with emission reduction/removal of one metric ton of CO2 from the atmosphere. Evaluators must ensure that there is no double counting of carbon credits- all operational carbon registries would need to be cross-checked. Carbon credits stored/retired with a carbon registry must be entirely traceable to the project which generated it. The registry must also ensure that retired credits are removed from the market. The challenge of double counting can also occur when two or more parties claim credit for the same emission reduction, breeding distrust in the VCM. Upcoming technological innovations such as blockchain technology are being deployed to trace the journey of carbon credits.

Principle 6: Independently verified

All emission reductions and removals should be certified by a recognised GHG crediting program and verified by an independent third party that attests that it has met all the criteria. For projects to be issued carbon credits they must be permanent and be able to demonstrate additionality. The verification mechanisms under standards such as Verra and Gold Standard are largely recognised as transparent and involve checks at multiple project stages.

Principle 7: Leakage Avoidance

The principle of leakage avoidance is a crucial aspect of the carbon market, particularly in carbon offset projects. Leakage refers to the unintended displacement of emissions from one area or activity to another, ultimately undermining the effectiveness of emission reduction efforts. The principle of leakage avoidance ensures that carbon projects take into account potential indirect emissions shifts and implement measures to prevent or minimise them. This involves carefully considering the broader system and the interconnectedness of activities, assessing the potential risks of unintended consequences, and implementing strategies to mitigate any leakage that may occur.

By adhering to the principle of leakage avoidance, carbon projects can ensure that their emissions reductions or removals have a meaningful and lasting impact, without simply displacing the problem elsewhere. Carbon leakages can be of two types

1. Local leakages: These refer to a situation where emissions are displaced from inside a protected (and monitored) area to a neighbouring unprotected area within the same jurisdiction. One way to monitor local leakages is to create a buffer zone (radius of 5 km) around the project and monitor deforestation in the ecosystem around the project using satellite-generated imagery.

2. Global leakages: These refer to a situation when emissions are displaced from one country to another due to variations in climate policies and regulations between countries. This relocation can result in increased emissions globally and is very difficult to monitor and quantify.

Often, emission-intensive activities are shifted to developing countries and least developed countries with less stringent climate policies. The European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) is being designed to prevent carbon leakage; under which the EU has imposed a high carbon levy on imported goods to prevent companies from shifting production processes to other parts of the world to avoid carbon emissions. The CBAM is projected to be introduced gradually around 2026, providing industries time to prepare for it while ensuring there is low market disruption. The levy will be imposed on goods from countries with less ambitious rules than the EU. On one hand, the policy design has been criticised on the grounds of limiting market opportunities for developing nations, on the other the EU claims that money collected through the levy will be channelled to less developed countries to help with the decarbonisation of their manufacturing industries.

Principle 8: Climate Equity

The principle of climate equity emphasises the importance of addressing social and environmental inequalities while pursuing climate mitigation efforts. It seeks to ensure that emission reduction projects contribute to broader sustainable development goals and do not exacerbate existing injustices. In the VCM, the principle involves transparently assessing project impacts on affected communities, prioritising projects that benefit marginalised populations, and empowering local stakeholders in project development. Additionally, it encourages projects that provide co-benefits beyond carbon reduction, such as clean energy access, job creation, and improved health.

By incorporating climate equity as a guiding principle, voluntary carbon markets can go beyond simple carbon offsetting and become a vehicle for positive change, promoting fairness, inclusivity, and the protection of vulnerable populations.

The voluntary carbon market is a vital tool in the global fight against climate change, allowing individuals, organisations, and businesses to take voluntary action and contribute to emissions reductions. However, to ensure its effectiveness and credibility, the market needs clear principles that govern its operations. These principles serve as guiding pillars providing a framework for evaluating and comparing carbon offset projects. They uphold transparency, integrity, and accountability, safeguarding the market against false claims, greenwashing, and unintended consequences. By adhering to these principles, the voluntary carbon market can maintain its self-governing nature, inspire trust among stakeholders, and maximise its potential in driving meaningful and impactful climate action. As the urgency of the climate crisis grows, the importance of these principles cannot be overstated, as they lay the foundation for a robust, transparent, and credible market that facilitates the transition to a sustainable and low-carbon future.